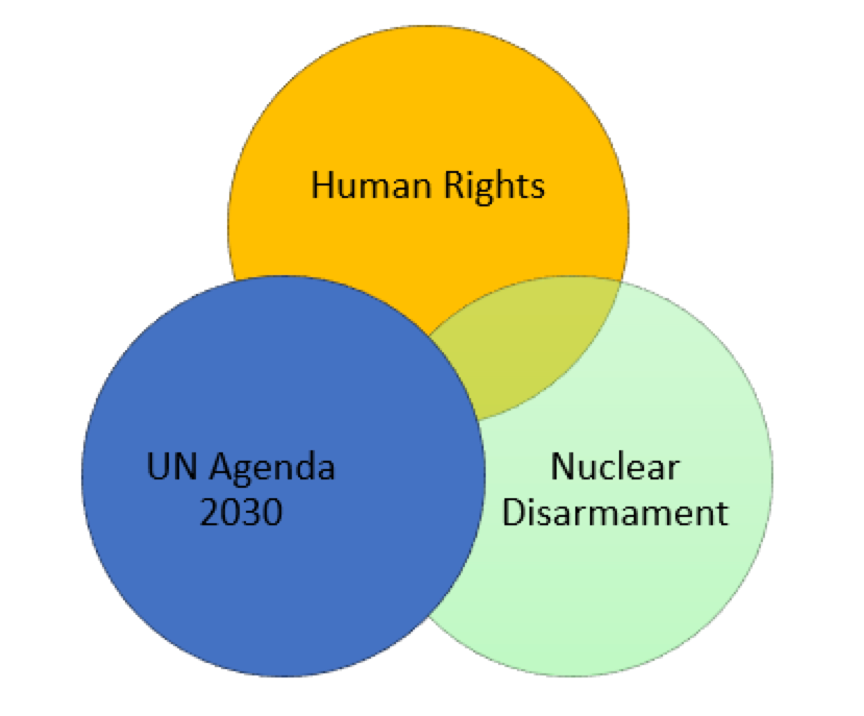

This article will be the first of three consecutive articles that, all together, highlight the most important challenges in the 21st century, and also various perspectives on how to link them. This article focuses on the connections between the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Human Rights. The second article will focus on the relations of Human Rights and nuclear disarmament, and the third will deal with nuclear disarmament and the SDGs. This systemic approach, which enables us to look closer into the interdependencies of the three topics, can be associated with the general principles of the Systems Thinking methodology. One fundamental goal of Systems Thinking is to appreciate the complex and messy world in which we live, so as to develop more effective solutions to critical problems – understanding that they are part of a broader system – rather than seeking simplistic and ineffective solutions which treat the problems in isolation.

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals were adopted at the United Nations General Assembly on the 25th of September, 2015. They are also commonly known as Agenda 2030. The goals as described in Agenda 2030, in and of themselves, reveal a complex network of interdependent aims: Whether it is to end poverty, to promote health care and gender equality, or to protect oceans and forests. It is, therefore, not possible to achieve one goal without making significant progress on others (read here more about the 17 SDGs). Systems Thinkers reject the notion that the 17 goals, or the many sub-goals, are discrete silos that can be slotted into small, separate boxes. Instead we must focus on the broad picture of 17 goals and the way they relate to each other in order to truly transform the world we live in.

Similarly, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the General Assembly in 1948, can also be seen as a complex set of interrelated rights and obligations, relating especially to the right of equality, freedom from discrimination and the right to life. By linking these rights in one document, the United Nations was able to achieve agreement amongst member states with different political priorities, legal systems and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world. If instead the UN had attempted to adopt the human rights individually, one-by-one, they would most likely have failed to achieve consensus on most, if not all, of them. This approach highlights the fact that the rights are indivisible. One sef of rights cannot be enjoyed fully without recognising the others.

We are now able to link one complex network, the Sustainable Development Goals, with another complex network, the body of universally recognised Human Rights. These networks can be seen as two sides of the same coin (more information is here). Progress by states on the SDGs, facilitates related progress on Human Rights, and vice versa. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) states that over 90% of Agenda 2030 goals are directly based on at least one Human Right. The Sustainable Development Goals provide an explicit plan to realise key rights embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, by the year 2030. One basic principle both networks share is the principal ‘Leave no-one behind’. This means that all humans on the planet are considered to have equal rights under human rights law, which includes the right to life, liberty and personal security. Governments and the international community have the duty to ensure the application of these rights to every person in every country. The principle to ‘leave no-one behind’ means that no-one should be left in abject poverty. No-one should be deprived of education, health and employment. No-one should have freedoms of speech, opinion and religion denied. And in connection with the SDGs, everyone has a right to live in an environment which sustains life.

What the Declaration of Human Rights embraces is not only rights, but also responsibilities. If we all have the rights under the declaration, then by logical inference we also have obligations to ensure the rights of others are upheld in addition to our own rights. This provides the key intersection with the SDGs, which outline our collective responsibilities to ensure the enjoyment of basic rights in a way that is sustainable.

To conclude, it is impossible to speak about Agenda 2030 without having the concept of Human Rights as a common basis. Furthermore, these interdependencies suggest a golden opportunity to become active and engage without having to take on everything. Each of us can choose specific SDGs or specific human rights for which we have interest or skills to make an impact, knowing that such activity will also benefit other human rights and/or SDGs. Making the connections between our area of focus and other human rights or SDGs builds cooperation and helps the system as a whole. In this way, the old notion ‘Think global, act local’ takes on new meaning and becomes ‘think global, act local, impact global.’

Author: Christoph Jaschek

This article is part one of a three-article series on Human Rights, Nuclear Disarmament and UN Agenda 2030. You can read the second article here and third article here.

Contact: christophj@pnnd.org